Joshiryoku: Japan’s Concept of “Girl-Power”

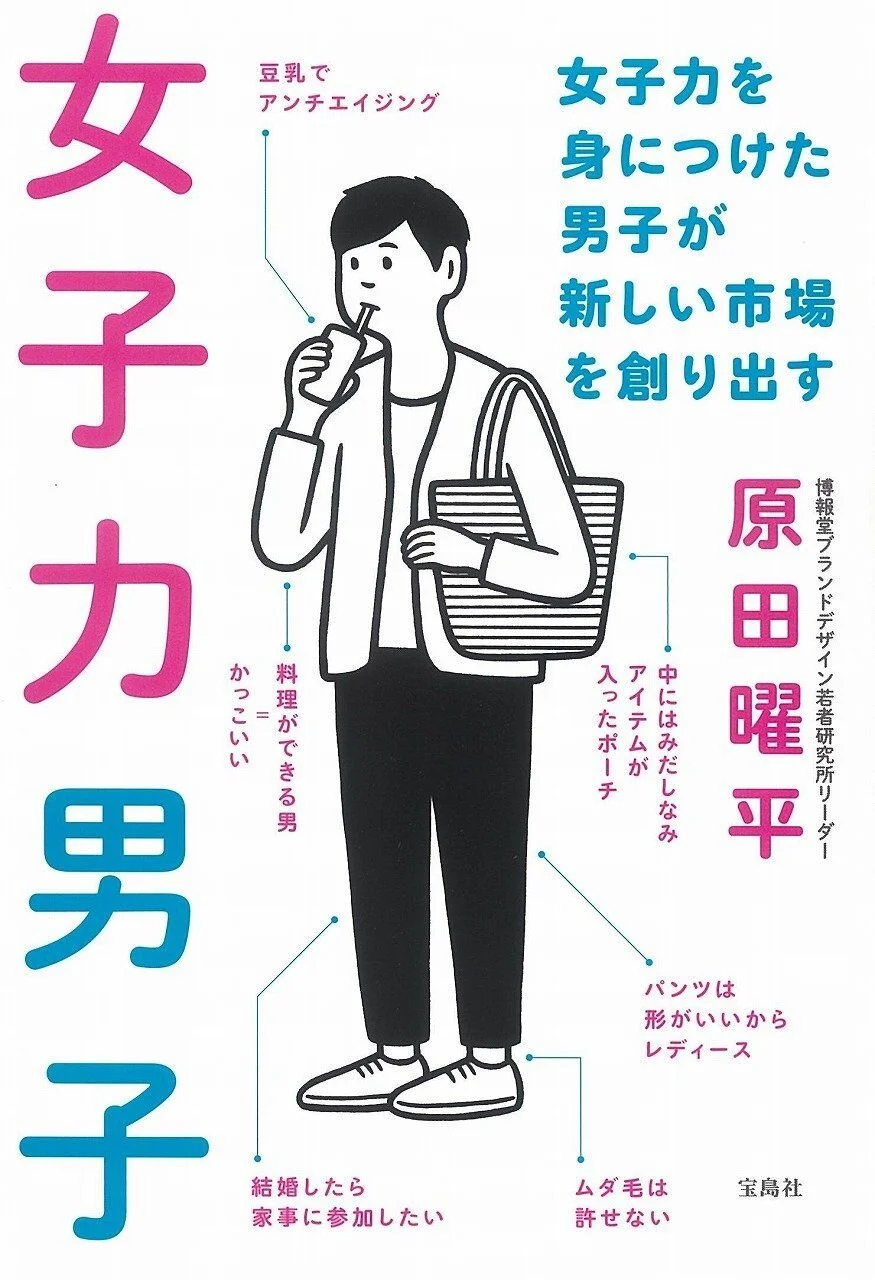

Fig. 1. Joshiryoku Danshi. Cover Art of the book Joshiryoku Danshi, Takarajimasha, Inc., 2014. Web. Accessed 12 Apr 2020. https://amzn.to/3a4LM98.

Gender performance was a concept that I encountered during my first year entering the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The notion that gender is not attached to specific sexes and that it is but an act that can be put on (Butler I) instantly connected with my internal narrative of personal history. Through childhood, I remember an intense desire to dress and act a certain way that was often described as tomboyish. Why it was unacceptable and must be corrected remained a mystery to me until much later in life. Butler's theory is so useful that it has become part of the everyday lexicon within the U.S. for the past several years. In this paper, I intend to examine the normalization of gender performances in Japan as I have experienced it.

Upon moving to Japan in 2015, the gender performance restrictions did not seem immediately clear to me. I have considered much of it, similar to Taiwan's expectations. However, one term that repeatedly struck me was "girl-power" or joshiryoku (女子力). The phrase was used by my peers to describe particular abilities that are considered feminine. At the time, I had maintained an active yoga practice, rudimentary training in barre exercises, and expressed an affinity and thus extensive knowledge for skincare. Upon sharing these hobbies with some friends, they have deemed that I possessed so much joshiryoku that we must make it a regular event to get together and do these activities. While I have never considered myself a very feminine person, the perceptions of my behaviors have arguably placed me differently than my understanding of self.

A few years later, I found myself not only familiar with the term joshiryoku, but I have also begun to use it on others. As I have learned, the term is not exclusively used on any individual of a particular sex or gender. Anyone can possess the so-called "girl-power," so long as they display behaviors that match the ideal of joshiryoku. For example, in 2014 a book on creating a new market for joshiryoku danshi, or "girl-power guys" was published to address this particular category of man. The book cover (Fig. 1) contains texts that are indicative enough of gendered values: "drinking soymilk for anti-aging benefits; men able to cook = attractive; if married would like to participate in household chores; does not tolerate body hair; because the pant shape is good therefore women's wear; [this bag] contains a pouch of grooming item." This list of items and beliefs is loaded with cultural-specific values highly associated with gender. In this sense, then, the term seems to be promoting an idea that is opposite of a restrictive understanding of gender. It appears to state that socially accepts traditionally-considered feminine practices to be done by anyone.

However, a closer look at the usage of the term will reveal that contemporary Japan is no genderless utopia; in fact, it is quite the opposite. Whenever an individual who is not a cisgender woman is described as having "high girl-power" (女子力が高い), it is often said in jest that makes fun of the said person. Although no harsh insult is spat, the implication is that the humorous moment is created by the contradiction between a perceived identity of an individual and behaviors that do not suit the expectations. In contrast, when the phrase is used on a cisgender woman, it becomes high praise. The corresponding implication is that such behavior matching societal expectations is to be praised and upheld. Returning to the caricature of joshiryoku danshi in Fig. 1, I consider that there is another message that is hidden within the image. Instead of broadening the range of acceptable behaviors for cisgender men, the laundry list of qualities is instead what is expected of women, by the virtue of using the term joshiryoku, for joshi within the vocabulary still means woman or girl. Of course not all woman or femme-identified individuals care about anti-aging properties in their drinks or carries grooming items with them on-the-go. Yet this framework is somehow still reinforcing and normalizing a set of gendered expectations.

Through gendered vocabularies like this, contemporary Japanese society is able to maintain a rigid two-gender system with specific aesthetics attached to each gender. Anyone fitting not into the defined sets of characteristics is thus "unmarked" (Murphy 87), using the vocabulary of Robert F. Murphy in his book The Body Silent. Murphy cites Erving Goffman in this discussion as follows:

Goffman used the phrase [the primal scene] to mean any social confrontation of people in which there is some great flaw, such as when one of the parties has no nose. This robs the encounter of firm cultural guidelines, traumatizing it and leaving the people involved wholly uncertain about what to expect from each other.

Although it may not be fruitful to compare the situation of a disabled person to those falling outside of the gender norm, I believe Goffman's idea of the primal scene can have similar manifestations when it comes to confronting unconventional gender presentations. When an individual does not have the "cultural guideline" to interact with another, awkwardness or even aggressive confrontations may ensue. In the case of Japan where genders are so strictly bound to a single image, those who are even slightly outside of it and thus gender non-conforming may encounter social interactions where these outlier qualities are addressed. The usage of the term joshiryoku is one of those instances.

Another notion of differences causing opposition comes to mind: Anne Fausto-Sterling's biological breakdown of the idea of sexes by examining intersex individuals and their stories. In "The Five Sexes", Fausto-Sterling writes, "Society mandates the control of intersexual bodies because they blur and bridge the great divide... [T]hey challenge traditional beliefs about sexual difference[.]" (Fausto-Sterling 24) Indeed, it appears that society often clings to the traditional structures that it is familiar with, and those who do not conform or those whose identities threaten these arbitrary categories.

The text "Romancing the Transgender Native" by Evan B. Towle and Lynn M. Morgan examines the problematics of using the "third gender" concept from other cultures in the West. This is an attempt by Westerners to normalize the idea of the non-binary gender system by invoking other various cultures, particularly those indigenous. It argues "that Western Binary gender systems are neither universal nor innate." (Towle 667) By presenting to an audience that there are multiple cultures with different concepts of gender, many hope to broaden what society considers "normal".

With any culture comes different concepts of gendered behaviors, and I believe that the borders that permeate gender expressions differ in quality according to cultures too. During the time I have lived in Japan, the concept of joshiryoku continues to fascinate me. I believe that although there may be space in exploring how can the concept of joshiryoku be used to dismantle the gender binary, it also currently functions to reinforce the gender binary in the contemporary informal lexicon. How we can creatively engage with the subject in order to utilize it remains to be seen.

Bibliography

Butler, Judith. “Performativity, Precarity and Sexual Politics.” AIBR. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, vol. 04, no. 03, Sept. 2009, pp. I–XIII.

Fausto-Sterling, Anne. "The Five Sexes: Why Male and Female Are Not Enough." The Sciences. Mar/Apr 1993, New York Academy of Sciences. pp. 20–25.

Murphy, Robert F. The Body Silent, New York, Henry Holt and Company, Inc, 1990.

Towle, Evan B. and Lynn M. Morgan. "Romancing the Transgender Native." The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York, Routledge, 2006. pp. 666—684.